Great Sphinx of Giza

History & Significance

The prevailing scholarly view dates the Great Sphinx to the Fourth Dynasty (around 2500 BC) and attributes its construction to the pharaoh Khafre. This theory is supported by archaeological evidence, stylistic similarities to Khafre’s pyramid complex, and the spatial integration of the Sphinx within the overall layout of the Giza Plateau. The head is commonly interpreted as an idealized royal portrait of Khafre, while the lion’s body symbolizes royal authority, strength, and protection.

At the same time, this attribution remains contested. Erosion patterns on the body of the Sphinx have fueled alternative theories suggesting a significantly earlier origin — possibly predating the dynastic period. While these hypotheses are heavily debated within academic circles, they underline one crucial fact: even in antiquity, the Sphinx was already the subject of restorations, reinterpretations, and profound religious significance.

During the New Kingdom, the Sphinx was revered as a divine entity, particularly as an embodiment of the sun god Harmachis. Pharaoh Thutmose IV erected the so-called Dream Stele between its paws, recounting how the Sphinx appeared to him in a dream and promised kingship in exchange for clearing it of encroaching sand. This narrative makes one point unmistakably clear: the Sphinx was never merely a monument, but an active political and religious symbol deeply embedded in the ideology of power.

Architecture & Dimensions

The Great Sphinx of Giza is the largest monolithic statue of the ancient world, carved directly from the natural limestone bedrock of the Giza Plateau. Measuring approximately 73 meters (240 feet) in length, 19 meters (62 feet) in width, and around 20 meters (66 feet) in height, its sheer scale was designed to overwhelm, dominate, and endure. The body follows the elongated proportions of a recumbent lion, while the head was carved separately from a harder upper limestone layer, allowing for finer detail and greater durability.

The monument is oriented precisely east–west, facing the rising sun. This alignment is not accidental: in ancient Egyptian belief, the east symbolized rebirth, renewal, and divine order. The Sphinx’s gaze toward the horizon reinforces its role as a solar guardian, eternally linked to the cycle of the sun and the concept of kingship as a cosmic duty rather than a human privilege.

Construction techniques reveal a highly calculated process rather than a single carving event. Tool marks and quarry cuts indicate that the body was shaped in stages, with blocks removed from around the statue and reused in nearby temple structures. The varying quality of limestone layers explains the uneven erosion visible today — a structural reality of the geology, not evidence of poor craftsmanship.

From an architectural standpoint, the Sphinx is less a statue than a sculpted landscape element: a fusion of natural rock formation and symbolic design. Its power lies not in decorative complexity, but in controlled proportion, axial placement, and absolute permanence — a deliberate statement carved into the terrain itself.

Head, Body & the Missing Nose

The Great Sphinx combines two of the most powerful symbolic forms in ancient Egyptian iconography: the lion and the human ruler. The lion’s body represents strength, dominance, and guardianship, while the human head signifies intelligence, authority, and divine kingship. This hybrid form was not decorative — it was ideological, presenting the pharaoh as a being that transcended human limits.

The proportions between head and body appear unusual to modern observers, with the head notably smaller than the massive lion form. This imbalance is intentional rather than accidental. Geological analysis shows that the head was carved from a harder layer of limestone, limiting its possible size, while also ensuring greater long-term preservation. The result is a visual hierarchy where the body conveys power and permanence, and the head conveys identity.

The most famous missing feature of the Sphinx is its nose. Contrary to popular myth, there is no credible evidence that it was destroyed by Napoleon’s troops. Historical drawings from the Middle Ages already depict the Sphinx without its nose. Most scholarly interpretations attribute the damage to deliberate iconoclasm, likely during the medieval period, when facial features were intentionally defaced for religious reasons.

Traces of pigment found on the surface indicate that the Sphinx was once painted, most likely in red and ochre tones for the body and darker colors for the facial features. This reinforces the idea that the Sphinx was originally far more vivid and visually striking than its weathered stone appearance suggests today.

Restorations & Damage

The Great Sphinx has never existed in a pristine, untouched state. From ancient times onward, it has been repeatedly buried by sand, exposed, repaired, and reinterpreted. Far from being a sign of neglect, this continuous cycle of damage and restoration demonstrates the monument’s lasting cultural and religious importance across millennia.

Evidence of restoration dates back to the New Kingdom, when large sections of the Sphinx’s body were already eroded. Stone blocks added around the paws and lower body show that ancient Egyptians actively worked to preserve the monument. These early interventions were not cosmetic; they were structural, intended to stabilize weakened limestone layers and protect the statue from further deterioration.

The primary cause of damage is geological rather than human. The Sphinx was carved from layered limestone of varying quality, with softer strata particularly vulnerable to wind, sand abrasion, and salt crystallization. Temperature fluctuations and groundwater exposure have further accelerated surface decay, especially along the lower body and flanks.

Modern restoration efforts, particularly in the 20th century, were not always successful. Some repairs used cement and incompatible materials that trapped moisture and worsened erosion. Later conservation projects corrected these mistakes by removing harmful additions and replacing them with limestone closer to the original composition.

Today, the Sphinx stands not as a frozen relic of the past, but as a visibly layered monument — its surface recording centuries of environmental stress, human intervention, and evolving preservation philosophy. Its current condition is not a flaw, but a historical document carved in stone.

Location on the Giza Plateau

The Great Sphinx occupies a highly strategic position on the southeastern edge of the Giza Plateau, directly aligned with the pyramid complex of Khafre. It is not an isolated monument, but an integral component of a carefully planned ceremonial landscape designed to express royal power, cosmic order, and divine legitimacy.

Facing due east, the Sphinx looks toward the rising sun, reinforcing its association with solar deities and rebirth. This orientation establishes a symbolic axis between the Sphinx, the valley temple, the causeway, and the pyramid itself — a spatial narrative linking the earthly realm to the divine.

The placement also serves a visual function. From ground level, the Sphinx appears as a guardian figure marking the threshold between the cultivated Nile Valley and the desert necropolis. Its position amplifies the monument’s psychological impact, controlling sightlines and guiding movement through the plateau.

Within the broader context of the Giza Plateau, the Sphinx acts as a focal anchor. It visually and symbolically binds the pyramids into a unified complex rather than a collection of standalone structures. This integration is essential to understanding the site as a single, intentional expression of royal ideology.

Modern visitors often underestimate this spatial logic due to contemporary pathways and viewing platforms. In its original context, the Sphinx was meant to be encountered gradually, emerging from the landscape as a controlled revelation rather than an immediately visible object.

Visiting the Sphinx Today

Today, the Great Sphinx is accessed as part of the Giza Plateau archaeological area. Visitors do not enter the monument itself; the experience is defined by controlled viewpoints, walking paths, and changing sightlines rather than physical proximity. Understanding this in advance is essential for realistic expectations.

The primary viewing area is positioned slightly above and to the side of the Sphinx, offering a clear frontal perspective and unobstructed views of the head, chest, and forepaws. Additional angles along the pathway reveal the full length of the body and its relationship to the surrounding temples and pyramids. Close-up access to the face is limited, primarily for preservation reasons.

Lighting conditions strongly affect the experience. Early morning provides softer light and clearer detail, while late afternoon emphasizes shadows and texture, especially along the eroded body. Midday light is harsh and flattens surface detail, making photography less effective.

The Sphinx is almost never experienced in isolation. Crowd levels vary, but complete solitude is rare outside the earliest hours. The monument’s scale and symbolic presence remain intact despite this, provided visitors approach it as part of a wider landscape rather than a standalone object.

Viewed correctly, the Sphinx is less about duration and more about orientation — where you stand, what you see first, and how the monument reveals itself in relation to the plateau. It rewards deliberate observation, not prolonged time on site.

Opening Hours & Access

The Great Sphinx is accessible during the standard opening hours of the Giza Plateau. There are no separate hours for the monument itself. In practice, the site opens in the morning and closes in the late afternoon, with last entry typically allowed well before closing time.

As a rule of thumb, visitors should plan their arrival for the early morning hours. This not only increases the chance of smoother entry but also provides better lighting conditions and more manageable crowd levels. Midday visits are possible, but heat, glare, and tour group density significantly reduce the quality of the experience.

Access to the Sphinx viewing area is included with the general Giza Plateau entrance ticket. Once inside the plateau, visitors reach the monument on foot via designated paths. The walking distance is moderate, but the terrain is uneven, exposed, and largely without shade.

Security checks and ticket validation take place at the plateau entrances. During peak hours and holidays, short queues are common, especially for independent visitors without pre-booked tours. Guided tours often streamline this process by coordinating entry times and movement across the site.

Because opening hours and access rules may change due to weather conditions, conservation work, or official events, it is strongly recommended to verify current times shortly before your visit — particularly if you are planning a tight schedule or combining the Sphinx with other attractions on the same day.

Tickets & Tours

The Great Sphinx is not accessed with a standalone ticket. All visits are part of the Giza Plateau experience, which means choosing the right ticket or tour directly affects how efficiently and comfortably you will see the monument.

Standard Giza Plateau entrance tickets are best suited for independent travelers who want full flexibility. They include access to the Sphinx viewing area and the surrounding plateau but provide no on-site explanation. Visitors should be prepared to navigate the site on their own and manage timing and crowd flow independently.

Guided tours including the Sphinx and the pyramids offer the most complete experience. A professional guide provides historical context, explains architectural relationships, and helps visitors understand what they are seeing — something signage alone cannot deliver. These tours are particularly valuable for first-time visitors.

Combined and skip-the-line tours are designed for efficiency. They typically include the Sphinx, the pyramids of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, and may also cover temples and panoramic viewpoints. Pre-booked time slots reduce waiting times and simplify logistics during busy periods.

Private and early-access tours provide the highest level of control and comfort. They are ideal for visitors who want to avoid crowds, optimize photography conditions, or follow a personalized route across the plateau. While more expensive, they deliver the most focused and uninterrupted experience.

Below are recommended ticket and tour options that include access to the Great Sphinx as part of the Giza Plateau visit:

Visitor Tips & Photography

Visiting the Great Sphinx is less about time spent on site and more about timing, positioning, and preparation. Small decisions — when you arrive, where you stand, and how you move — have a disproportionate impact on the quality of the experience.

The best time to visit is early in the morning. Temperatures are lower, light is softer, and crowd levels are significantly more manageable. Late afternoon can also work well for atmosphere, but glare and tour congestion tend to increase as the day progresses.

Photography is allowed from designated viewing areas only. A wide-angle lens is useful to capture the full scale of the monument, while a medium focal length works best for framing the head and forepaws. Midday light is harsh and flattens surface detail; morning and late-day light reveal texture and depth.

Because shade is extremely limited, sun protection is essential year-round. Comfortable walking shoes are strongly recommended due to uneven ground and extended walking distances across the plateau.

Expect a lively environment. Vendors, guides, and other visitors are part of the experience. Staying focused on sightlines and ignoring distractions helps maintain a more immersive impression of the monument.

Finally, avoid rushing. The Sphinx is best appreciated by slowly adjusting perspective — stepping back, changing angle, and observing how it interacts with the surrounding landscape rather than treating it as a single photo stop.

Nearby Highlights

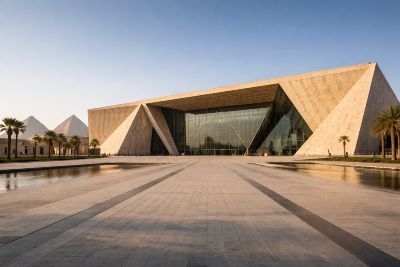

Giza Plateau

Grand Egyptian Museum